-

On a cold and quiet morning, the sun shines down from a clear blue sky, piercing through pine and cypress leaves, coloring patches of the forest’s undergrowth.

-

The seed collectors move up the mountainside, their breath coming in quick bursts. Their shoes are damp with the morning dew; their backpacks loaded with collecting gear. They keep pace with their local guide, Don Marcelino, who stops briefly under a tree, quickly scans the undergrowth, and moves on up the slope.

-

Below in the distance, a dirt road snakes across the opposite mountain range. Tiny figures tend to the dozens of potato plots that pocket the land in perfect squares. This is potato country in Guatemala, the province of Huehuetenango. It is also home of Solanum clarum, a potato wild relative.

-

Find them if you can: Searching for wild relatives in Central America

A wild potato, bean, eggplant and rice saga

Text & Photos: LM Salazar

-

Potato is the third most widely eaten food crop in the world. Like rice, beans, maize and wheat, it is a staple crop.

But climate change is making it harder for farmers to grow potatoes – be it Guatemala or Zambia, China or the USA, or anywhere else in the world.

-

“If we are to feed a growing population, we need to make our food crops more resilient,” says Marie Haga, Executive Director of the Crop Trust. “And crop wild relatives can help breeders develop new ‘climate-proof’ varieties.”

-

Crop wild relatives have sturdy traits, like tolerance to drought, flooding or different diseases, which can help potatoes, as well as other crops, adapt to new challenges. But to use them, we must first collect and conserve them.

-

“Despite the historic efforts to conserve them, many important wild relatives are still underrepresented in, or altogether missing from ex situ collections,” says Nora Castañeda-Álvarez, Genesys Catalog Coordinator at the Crop Trust, who was the lead researcher in the global study on crop wild relatives ex situ conservation priorities.

-

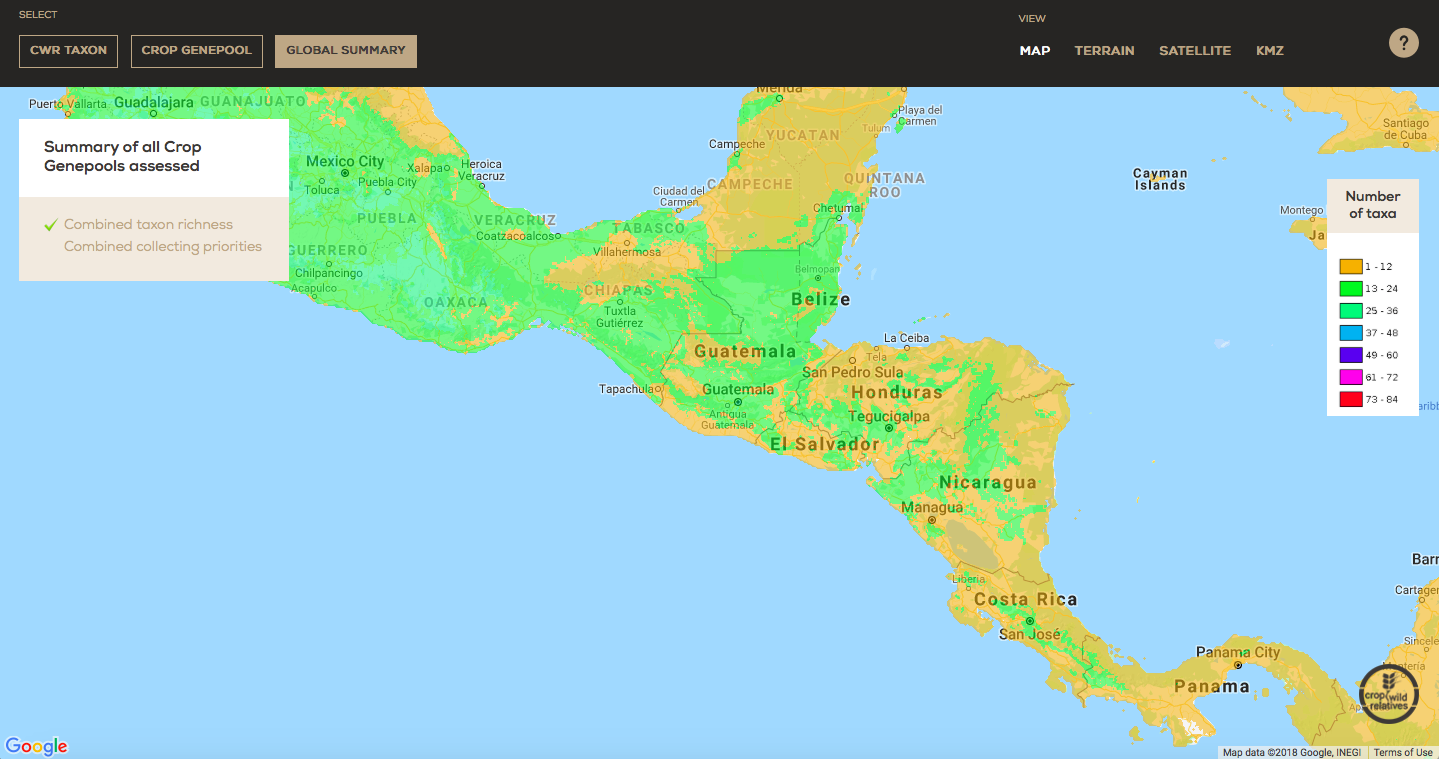

This study mapped out – and steered — the collecting challenge the CWR Project has undertaken; starting in 2013 and working with 24 national partners, the project aims to collect wild relatives of 28 crops.

-

Central America is home to 7% of the world’s biodiversity. Here, teams in Guatemala and Costa Rica are doing their part in collecting crop wild relatives, traveling long hours over lonely, often dusty and bumpy roads to distant locations.

-

Mosquito-infested marshlands; cold cloud forests; breathtaking natural reserves; as well as large and small farmers’ fields – these are some of the places collecting teams must explore.

-

In Guatemala, our partners at the Guatemalan Institute of Science and Technology (ICTA) work with a wide range of stakeholders, including indigenous farming communities and universities to collect the wild relatives of six key crops for food security: beans, potatoes, sweetpotatoes, eggplant, barley and rice.

Three of these – beans, rice and potatoes — are staple foods to Guatemala’s 16.8 million people.

-

— Solanum clarum —

The wild potato Solanum clarum grows in cloud forests between 3,100 and 3,800 meters above sea level.

Underrepresented in ex situ collections, with a total of only 21 accessions held in four national institutes – USA (15), Russia (3), Germany (2), and Ukraine (1) – Solanum clarum is one of the more than 20 wild relatives that the ICTA team is determined to find and collect.

-

Today luck has struck, as it appears that the team has found it, nestled amongst some moss.

-

“Many of the areas we visit are in or near indigenous communities where it is more common to speak Kaqchikel than Spanish,” says Delmy Castillo, who works in the ICTA’s Genetic Resources department.

-

The ICTA team often relies on local guides, which is common in rural areas all over the world. In fact, rural communities are sometimes key collaborators in these expeditions.

-

— Phaseolus coccineus —

Like Solanum clarum, Phaseolus coccineus subsp. coccineus (a wild relative of beans), is underrepresented in the world’s genebanks. It’s a climbing plant that flowers between September and November.

-

“In Guatemala, this species can be found in the central and western plateaus, in cold environmental conditions, between 1800 and 3000 meters above sea level,” says Marielos.

-

Finding a wild relative is no walk in the park. Some species are hard to find, as they often grow in far-removed, unwelcoming places, under extremely harsh conditions. Others grow at the side of roads and trails, in farmers’ fields, at urban frontiers or on coastal edges.

-

From the highlands of Huehutenango, where “nothing but potatoes grow,” as Marielos says, to the jungles of El Petén, home of the Mayan Tikal ruins, to the hot and humid Pacific Coast, the ICTA team journeys for days at a time.

-

This photograph was taken from a small makeshift bridge, as the ICTA team walked down a trail towards a farmer’s home. They were searching for Solanum torvum (an eggplant wild relative) when they stumbled upon this Phaseolus coccineus, growing at the side of a stream, in el Triunfo Sector near Sololá.

-

Collecting wild relatives takes planning, patience and perseverance.

“You must study where past collections were carried out — if any have been made. You must familiarize yourself with the plant, looking at herbarium specimens, photos, descriptions.

-

Once you are in the field, you must keep your eyes on the ground, and search as thoroughly as possible. You get better at it with time. But you also need a little luck,” says Marielos.

-

In this photo, the ICTA team has found a large population of Phaseolus parvifolios. The plant is in its flowering stage, probably three months away from the seed collecting stage,” says Marielos. “We’ll have to come back to collect seeds.”

-

Coming back to a spot is part of the collecting process. “The teams are after optimal seed, this means the collecting needs to happen at just the right moment – not before, not after,” says Hannes Dempewolf, Senior Scientist at the Crop Trust.

-

Unfortunately, sometimes, when collectors return to a site, the seed is no longer there. A horse (in this case) or a cow or a goat can be to blame, having eaten the plant, or its flowers or seeds.

-

Other threats to wild relatives include invasive species, land degradation, urban expansion and agriculture. During their collecting expeditions, the ICTA team has found wild beans at the edge of sugarcane plantations, as pictured here.

-

“This is the reason why we must act now, and safeguard these species while we can still find them in nature”, says Marielos.

-

— Solanum torvum —

The ICTA team is also hunting for wild relatives of eggplant, a member of the genus Solanum, and a distant cousin of tomatoes, potatoes and peppers.

-

Eggplant is also a native of the tropics, but not the Americas. It was probably domesticated in Southeast Asia, and it is an important source of micronutrients and dietary fiber.

-

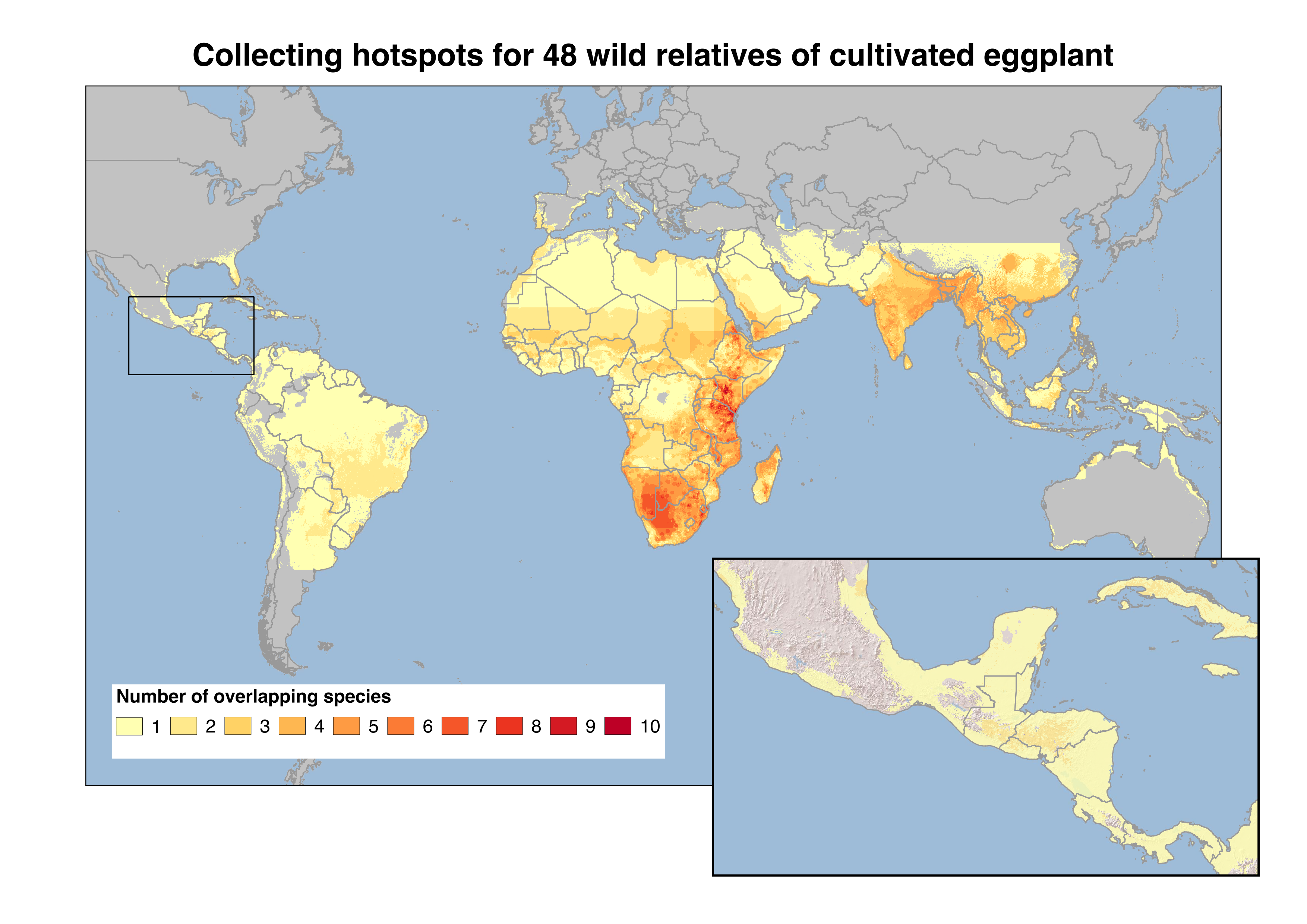

According to the study of crop wild relatives ex situ conservation priorities, 40 out of the 52 wild relatives of eggplant are in urgent need of collection.

-

“Spots of richness of these wild relatives are mainly found in Africa and Asia,” says Nora. “However, Solanum torvum, a wild relative known for its resistance to biotic stresses (such as bacterial and fungal wilts, and nematodes) can be found in Central America.”

-

In Guatemala, Solanum torvum is considered a weed and can be found at the side of highways and roads, trails and ravines.

-

Pictured here, the ICTA team studies a large, healthy population of Solanum torvum, found next to a maize plot, at the side of the highway that leads from the municipality of Chiantla to Todos Santos, Huehuetenango.

-

Sometimes, before any collecting has even started, exploratory trips are carried out to pinpoint the hotspots of these wild populations.

-

“These exploratory trips allow us to determine if the plants are ready to be harvested. That helps us plan the optimal time to come back and collect the seeds,” says Delmy.

-

“If we collect too early, there is a risk that the embryo is immature, which means the seeds would not germinate,” explains Delmy.

-

Michael Way, Conservation Partnership Co-ordinator (Americas), Millennium Seed Bank at Kew, adds: “If they arrive too late, the seed may be lost completely, victim to pests or animals. The CWR Project Collecting Guides help them to plan expeditions at the correct time of the year”.

-

In the photos: Wild eggplant (left) and wild potato fruits, in Guatemala. When first found, they were not in the optimal state for collecting.

-

“The CWR Project Collecting Guides have proven to be a great resource,” says Marielos. “Out in the field, we look at the physical characteristics of a plant: small purple inflorescences; creeping habit. And we compare these to what appears in the CWR Project Collecting Guide.”

-

To be 100% sure that what has been collected is indeed what they are looking for, seed collectors prepare a herbarium specimen during their exploratory trips.

-

“A herbarium specimen allows botanists to check the identification features of the plant carefully, and confirm the correct name to use for the collection,” says Michael.

-

Throughout the many stages of a collecting effort, it is crucial to gather comprehensive field data.

-

“This includes details of the location and habitat, to help researchers – the future users of this diversity – understand the potential use and value of the material,” adds Michael.

Pictured: Herbarium specimens of wild eggplant (left) and wild beans collected in Guatemala.

-

— Oryza latifolia —

In the north of Costa Rica, rice is a prominent crop. It has been so for more than 30 years, in large part thanks to the creation of a large-scale irrigation program in the Guanacaste province.

Guanacaste is also considered to have the most fertile “micro-zone” in the country, and produces 32% of the nation’s rice, according to 2013 statistics from the Ministry of Agriculture.

-

“If you ask me to give you a percentage of how important rice is for food security in Costa Rica, I would say it is around 90%,” says Pedro Gonzales, a farmer in the Guanacaste region. “The other 10% goes to whatever else we have at hand that is edible.”

-

Mr. Gonzales says his last two harvests have suffered decreases in both yield and quality. “I blame climate change for this,” he stated.

-

Oryza latifolia, commonly known as “arroz pato” in Costa Rica (or “duck rice”), can be found in protected areas and rice fields. Farmers consider it a “contaminant” rice.

-

If this “duck rice” is not controlled in rice fields, its populations increase in density and impairs the quality and growth of cultivated rice. Farmers sometimes use herbicides to eliminate it from their fields.

-

Though it may be considered a weed, O. latifolia has positive traits, too. It is resistant to brown planthopper, for example, which in the 1960-70s became the biggest threat to rice production in many parts of Asia (IRRI, 1979).

-

Our CWR partners at the University of Costa Rica (UCR) understand its value and are busy collecting Oryza latifolia. They are also collecting O. glumaepatula, which has high-yield characteristics, and O. grandiglumis, which has high biomass production.

-

In this photograph, the UCR collecting team, Marcela Turcios, and Griselda Arrieta, who work at the Research Center in Molecular and Cellular Biology, collect an O. latifolia sample in a farmer’s field.

-

“Farmers are happy when we collect these plants,” says Marcela. “For them, we are eliminating a plague. But the idea of us investing time and effort in collecting something that for them has no value, perplexes them. So, we try to explain to them the importance that these ‘weeds’ have, and the need to conserve them.”

-

Why collect the whole plant? Because the amount of seed produced by O. latifolia is very low, and when the fruit ripens, the seeds naturally disperse.

-

These specimens are therefore kept in greenhouses in order to multiply seeds, and reach the large numbers needed in the overall collecting effort.

-

Back in 2016, Marie Haga and Hannes Dempewolf from the Crop Trust visited the CWR Project partners in Central America. In Costa Rica, they saw first-hand what challenges the UCR team faces in order to find and collect Oryza latifolia.

-

“Marie and Hannes joined our 6th trip of the year,” recalls Marcela. “By then we had collected 34 samples of O. latifolia plants, 15 of which were collected in Guanacaste.”

-

The others were collected in the provinces of Puntarenas and Limón. The former is in the South-Pacific side of the country; the latter is on the Atlantic side, extending the length of the country, from Nicaragua down to Panama. In short, the expeditions cover most of the country’s terrain.

-

By the end of the project, the UCR team expects to have collected 53 populations of O. latifolia, 15 of O. glumaepatula and eight of O. grandiglumis.

-

“Collecting missions require stamina – getting required permissions is not easy, and doing the actual collecting in demanding and partly unfriendly environments is more than challenging.”

Marie Haga

Executive Director of the Crop Trust -

Time and land-usage: according to GPS coordinates, someone once collected wild rice in the location photographed here. Now, there is nothing but sugarcane fields.

-

In their expeditions, Griselda and Marcela visited other past collecting sites, locations where former seed collectors had found wild rice. 30-odd years later, Griselda and Marcela found tilapia ponds, houses, concrete and asphalt roads, but no wild rice.

-

While many of these past sanctuaries no longer exist, there are 11 conservation areas protected by government institutions in Costa Rica.

“O. latifolia and O. grandiglumis are found in these protected areas, and there these wild species do not face as many threats as other species,” says Griselda.

-

“The largest populations of O. latifolia are found in the Palo Verde National Park (pictured here), located in Guanacaste, along the Tempisque River. In the Atlantic coast, they are found in the Tortuguero National Park, in Limón.”

-

Nightfall signifies the end of a long collecting day.

Here, at the mess hall of the Palo Verde National Park, the team regroups and unwinds, discussing the next day’s plans, as well as the project’s progress and challenges.

-

“Visiting our national partners, and accompanying them as an observer on a collecting mission, allows us to better understand the realities they face out in the field,” says Hannes, pictured here with Marcela and Griselda.

-

In Panajachel, Guatemala, Hannes discusses the administrative aspect of the collaboration with Marielos.

“It may not be as exciting as hiking through a picture-perfect scenery, but it also must be done,” he says.

-

Collecting crop wild relatives in Central America is a big job for a small group of people who, each in their own way, contributes to a more resilient food system.

Here are a few of the faces that are at the forefront of the CWR Project collecting and conservation efforts.

-

“It is their commitment that we applaud,” says Marie Haga. “And we thank their unwavering perseverance.”

-

Perseverance. “Perseverance is synonymous with patience, resolve, tenacity – all key ingredients to carry out the collecting duties,” says Delmy.

“It’s a huge effort to find even just one population of a wild relative, but at the end, one has the satisfaction of a job well-done, and of contributing to safeguarding our wild species.”

-

This photograph was taken in el Triunfo Sector, in the hills near Sololá, Guatemala, the moment Delmy confirmed the purple flower shown here was indeed from a sweetpotato wild relative.

-

This was possible thanks to the support provided by her guide / translator, Bartolo (left), and Cruz Palax, a local farmer (middle) who, upon looking at a picture of a flower in the CWR Project Collecting Guide, disappeared for a quick minute behind a thick wall of vegetation and came back with the real thing in his hands.

-

In Central America, and beyond, there is still a lot more work to be done – within and beyond the project. Most partners have already finished their collecting efforts, while others like the teams in Guatemala, Costa Rica and partner countries will work until the end of this year, when the collecting phase of the CWR project comes to an end.

-

For now, they are still in the field, searching and finding these elusive wild relatives. “And when the seeds are ready for collecting,” says Griselda, “we will be there.”

Marcela adds: “It is gratifying to know that the work we are doing can have a great impact for the future of humanity.”

-

It takes a special kind of person to do what CWR collectors do. They have to have a little of Indiana Jones in them – unwavering in their determination and committed to saving something that is priceless: plants that can help adapt our agriculture to new challenges.

-

It takes patience and persistence, time, a sharp eye, getting your hands dirty, and a lot of luck.

But someone’s got to do it, right?

-

.