-

Brazilians love potatoes but the domesticated potato they love isn’t native to Brazil. Potatoes originated from Peru, but the crop wasn’t introduced to Brazil from there; they came from across the Atlantic.

-

The Spanish conquistadores introduced potatoes from South America to their homeland in the 16th century and it wasn’t long before the tuber was being planted throughout Europe.

Three hundred years later, the British workers came to south-eastern Brazil to build the railways and demanded the potatoes they ate back home.

-

During this time, German settlers brought the potato to the south of Brazil. The Germans supplied the English with their daily share of potatoes and helped spread the crop to the rest of the country.

For the Brazilians, these foreign tubers were associated with the British. And still today, the potato is frequently called batata inglesa in Brazil.

-

But some wild cousins of the original domesticated Peruvian potatoes also grow in the wild in Brazil and seed collectors there are busy hunting for these species as part of the Crop Wild Relatives Project.

-

In Search of the Wild Cousins of the “Batata Inglesa”

Text by the CWR Communications Team

Images: LM Salazar -

Today, more than one billion people worldwide eat potatoes. In terms of global production, potato is the fourth most important food crop.

Potatoes come in all sorts of sizes, colors, tastes, and shapes. This incredibly diverse crop has more than 4,000 varieties.

-

Only a few varieties may appear in our supermarkets, but some indigenous communities in the Andes grow more than 200 varieties for home consumption.

-

There are more than 100 wild potato species found in South America and some of those are native to Brazil.

-

Wild potatoes may be too bitter to eat, but they hold traits that commercial varieties have lost during their domestication, including resistance to diseases, pests, and climatic stresses.

-

Last June, we visited our Brazilian collecting partner. EMBRAPA is one of 24 institutions the Crop Wild Relatives Project is supporting to collect seeds around the world – and fill the gaps in the world’s ex situ collections.

-

EMBRAPA collecting teams are focusing their efforts on the wild relatives of four crops: finger millet, potato, rice and sweetpotato. During our time there, we accompanied the wild potato collecting team, which is led by Gustavo Heiden.

-

Gustavo is based at EMBRAPA’s Clima Temperado station, in the city of Pelotas, Southern Brazil. It is one of 40 EMBRAPA stations, and the hub of all things potatoes in Brazil.

-

From conservation to breeding, to plant pathology research to nutritional studies, EMBRAPA aims to ensure that potato farmers in Brazil can continue producing this crop to meet increasing demand, in both quality and quantity.

No easy task.

-

The average temperature in southern Brazil has increased by 1.6 degrees Celsius over the last 50 years. This increase, along with rising rainfall and more extreme climatic events, is reducing potato yields.

-

Brazil is a primarily a tropical country, but potatoes are grown largely in temperate climates. The available production space is already limited, but now climate change is forcing farmers to move to cooler regions and higher ground.

-

But Brazilian farmers can’t climb mountains or head south endlessly in search of cooler growing areas. The future of potatoes rests in our ability to adapt them to higher temperatures. In other words, to tropicalize them.

-

The wild potatoes of Brazil could provide the key to this.

-

Gustavo planned a two-day expedition to search for the wild potato species, Solanum commersonii.

On the first day, we headed south, towards Chuí, a town which straddles the Brazilian border with Uruguay. We reached our first collecting site on the outskirts of the Taim Ecological Reserve.

-

A conservation area of worldwide importance, this site is a sanctuary for a huge diversity of plant and animal life, including the capybara, the largest rodent in the world.

-

Gustavo had planned our trip to coincide with the plant’s flowering season. And, indeed, the population we found was full of flowers.

-

This scraggly looking plant, fairly inconspicuous amongst the roadside debris, is resistant to root knot nematode, blackleg and soft rot. It has tolerance to frost and cold – a trait that is vital for growing potatoes in highland areas.

Unfortunately, there were no seeds. So we moved on, undeterred, towards Uruguay. Gustavo will be back, though.

-

We drove on to the Praia do Cassino/Hermenegildo, the longest beach in the world.

We then continued our search in dirt roads that cut across large grazing fields. Soon, Gustavo spotted one lone wild potato plant. But, again, no seeds.

-

In a final attempt, we turned back and walked along the road hoping that the slower pace might reveal something we missed the first time around.

-

Amazingly, in the carpet of green beneath our feet, Gustavo spotted another Solanum commersonii. Although flowers and fruit were absent, Gustavo found the plant had tubers, which we could take back to the research station.

-

“We keep everything we collect, as we don’t want to lose any diversity. These wild potato tubers will be grown and multiplied in a greenhouse and increase our potential diversity,” Gustavo explained.

-

“Previously, all this diversity was safe in the wild, but now we are running against the clock to conserve the diversity because it is getting lost in the grasslands,” said Gustavo.

“If the Irish potato famine happened today, we would rely on ex situ collections to find new resistant varieties, like the ones collected under this project.”

-

On the second day, we travelled north, and before long, we arrived at our destination: the Fazenda São Miguel, a 1700-acre family-owned rice and cattle farm that has set aside part of its land for in situ conservation. It’s like a private nature reserve.

-

Within minutes of arriving, Gustavo spotted a small purple flower that grew at the edge of a paddock just five meters from the family house. And with the flower, we found some small green fruits.

-

Jackpot.

It is what is nestled inside these fruits that brought us to Brazil: the seeds of a wild potato!

-

Finding the fruit is vital. Tubers from a plant are genetically identical.

-

But within one fruit there could be 50 seeds, and each seed can have a different genetic makeup. It is this genetic diversity that provides the greatest potential for crop improvement.

-

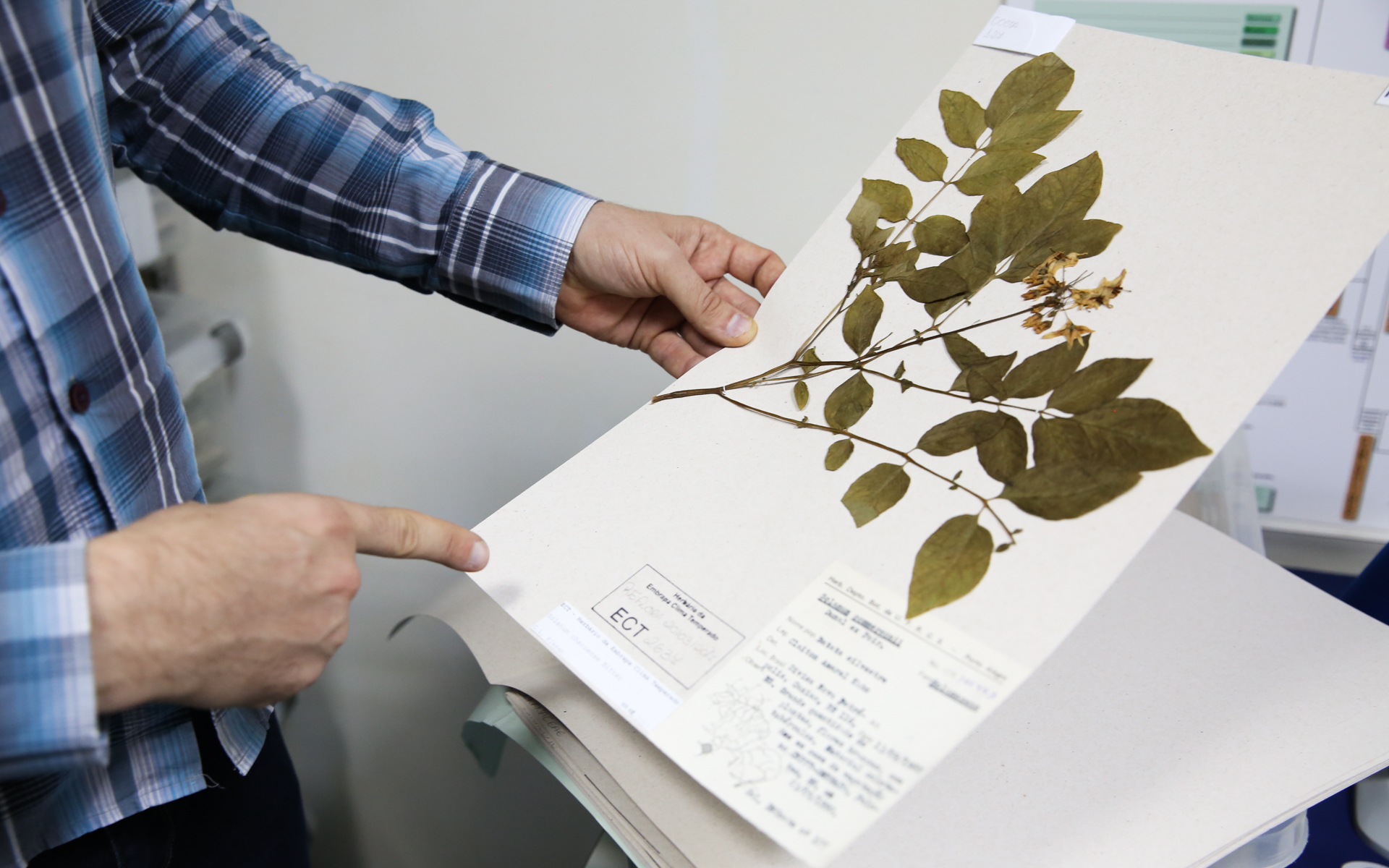

Along with the fruits, crop wild relatives collectors must also collect data about the plant and location and create an herbarium specimen – a pressed, dried sample of the mother plant, ideally including flowers, leaves, everything.

-

Each specimen can be used to develop and share knowledge about how to identify a species, where it can be found, and when it is in fruit. This information helps conservation efforts by allowing future researchers to figure out where and when to collect seeds.

-

When only a small number of seeds is collected in the wild, scientists collect tubers, grow the plants out and pollinate them by hand to produce enough seed to allow further conservation and research.

-

For EMBRAPA, this provides an opportunity to train students, like Isis Paglia and Matheus Vasconcellos, pictured here, who will inherit the ongoing, unsung, but vital, task of safeguarding our valuable genetic resources.

-

But how do scientists use this wild diversity, exactly?

Scientists first explore how domesticated and wild varieties can be crossed to develop new, more resilient varieties. This is called pre-breeding.

-

“The Crop Wild Relatives Project is coordinating pre-breeding efforts on 19 crops; it’s not something that many national research organizations around the world are doing, so it’s inspiring to see EMBRAPA doing their own pre-breeding work,” says Hannes Dempewolf, Senior Scientist at the Crop Trust.

-

Shown here is Guilherme Klasen evaluating controlled hybridizations of potato wild relatives.

-

“At this point, we may not know what traits the wild potatoes contain, but we are discovering which ones can be crossed with the crop. Results will help speed-up the breeding process that will allow the transfer of traits. This is the challenge,” explained Gustavo.

-

Breeding new varieties takes on average 12 years. But not 12 years of sitting back and waiting. EMBRAPA’s potato breeders – Arione Pereira, Fernanda Quintanilha Azevedo and Beatriz Marti Emygdio – are very busy the whole year round crossing, evaluating, multiplying seeds, analysing data. But that doesn’t keep them from the field.

-

“We can do our best at breeding, but if we don’t increase the gene pool and bring in new diversity we may lose our crops,” says Arione Pereira, EMBRAPA’s lead potato breeder.

“The wild material is critical in our efforts to develop climate-adapted varieties,” he adds. “Time spent in the field collecting wild relatives is never wasted.”

-

It is through global collaboration among dedicated plant scientists such as our EMBRAPA partners, that we as a global community are able to safeguard and make available the plants that hold the traits that will likely save our future crops. Who knows who else will use the seeds we collected in Brazil?

-

“Researching crop wild relatives requires patience and persistence,” said Gustavo. “I have at least 30 years left in my career, so I have time to work on this and hopefully see the benefits from the work we are doing now.”